This is a post in two voices that lives in two places. You can read the other version at Bud’s website. In this version, my voice appears in italics and @budtheteacher‘s is in the other.

It’s been a few weeks now since Katie Henry and I met up at reMAKE Education to run two sessions of a workshop that has me more excited than I’ve been about a workshop in a long time. I’ll get to the excitement part – but first, a bit on how this came to be.

It’s actually quite a story. And it starts, not with a conference proposal, but with a business card. No, that’s not true. It begins with a brownie.

I could see them there on the plate in the corner of the kitchen. And they looked pretty good. So I made my way towards them, eager to confirm my observation.

Katie was standing in front of the brownies. A better person would have introduced themselves and then excused themselves to get to dessert. I’m pretty sure I did it the other way around.

_______

He did.

_______

As I learned a little more about what Katie does, we exchanged cards and a promise to follow up. That’s a common conversation in my world – and many such don’t lead beyond a couple of links exchanged. But with Katie, I was intrigued.

As I got to know her more, I could tell that while her background is different from mine, we both seem to approach the raw materials of learning and the role of learners in learning experiences in similar ways. She’d say something like “the mindset matters more than the material.” And I’d agree. So much of the “stuff” of learning, the things in the classroom, the library, the makerspace, etc, gets too much front end attention. Mastering the stuff isn’t the goal or the outcome. The raw materials are invitations, ways of starting and seeing, and making thinking visible. I could tell pretty quickly that Katie approaches most learning experiences as invitations.

I dig that.

_______

The day after Bud Hunt ate a brownie before he said hi, I was at the Portland airport to fly home to Pittsburgh. Frustrated with the rude machine at the Southwest terminal, I was surprised to see Bud walking past. Apparently we both had 6AM flights on Southwest, though his was taking him home to Colorado.

Bud saw that the machine was ignoring my request to print boarding passes, though instead of consoling me or getting frustrated alongside me (in an attempt to empathize) or anything else, he said, “It’s Southwest.”

He just stated a fact, “It’s Southwest” in such a way that I suddenly felt compassionate towards the airline I knew and loved.

He didn’t try to teach me anything. Or fix anything. He stated a fact in an understanding, compassionate, and patient way that allowed me to shift my own heart and mind towards my own situation.

This might not seem like a big deal, but when it comes to meeting people where they are, the best teachers know how to say the fewest words and have the biggest impact.

As Parker Palmer writes, “Good teachers join self, subject, and students in the fabric of life because they teach from an integral and undivided self; they manifest in their own lives, and evoke in their students, a “capacity for connectedness.”

Bud does that.

_______

Too many of the folks I come across in my day to day interactions in schools are still far too comfortable with the idea that subjects happen in separate rooms, and that history and science and language arts and whatever the hell ST(R)E(A)M is this week ((Because it sure seems to change depending on where I am and who I’m talking to.)) are disparate bodies of knowledge that rarely intersect.

That’s not how learning works.

At my core, I’m a writing teacher because I believe that writing, composition, is one of the fundamental ways of learning. And at school, writing across the curriculum is far too often “write about how the thing we just did made you feel.” Which isn’t a bad prompt. But that shouldn’t be the be all and end all writing to learn experience of school. It really shouldn’t at all be the way that writing or composition or creation enters into a learning process – at the end, after all of the “learning” is done.

What if composition were there the whole time? Is that where the learning happens?

As Katie does when she puts pieces together, she invited me into a conversation with some of the folks at the Sonoma County Office of Education. Casey Shea wanted to explore the idea of maker networks in a similar vein to the National Writing Project network, and I’ve explored that a bit. He brought Kelly Matteri along because of her language arts expertise. So I found myself in a conversation with Katie and Casey and Kelly, talking about the intersection of writing and making. And when Kelly mentioned that she really wished that someone would “Ada Lovelace” up the intersection between computing and robotics and writing, well, Katie sprang into action.

The gist of her response was, “I think Bud and I should try to do that.”

_______

Although, the reality is that I already observed Bud to be doing this, just with other tools.

_______

It was a bit of a surprise, because that conversation didn’t really begin with “let’s do a workshop” so much as “let’s share some ideas.” But, as I’m learning, Katie doesn’t mess around when she sees something worth doing. It’s one of many reasons I like working with her. She can see things before other people can.

_______

A good teacher understands student misconceptions and begins to fiddle with experiences that might allow the learner to construct new and more complete knowledge.

An even better teacher understands their own misconceptions and begins to fiddle with experiences that might allow herself to construct new and more complete knowledge.

The best teachers never stop doing either of these things.

I saw working with Bud on this project as a way to fiddle with experiences that would help me to become a better teacher of teachers.

He’s a good teacher.

_______

So there we were, trying to figure out how to build a workshop around writing and robotics that wasn’t something like “Build a robot and then write about how it felt to build a robot.” Because where’s the fun in that?

_______

Isn’t composition there the whole time? It’s where the learning happens.

_______

It didn’t take long for us to center on the intersection of poetry and robotics. Ada Lovelace, after all, lived in the intersection of poetry and computing ((Or at least the romanticized version of her did. And still does.)). There were fortuitous turns along the way.

I had plans to build the Metaphor Muse, so I was already thinking about poems and machines in some useful ways. And Katie had been working on a project around memories and robots, so there was that, too. Later, I would lean on her expertise with MakeCode to help me get the Muse to behave the way I wanted it to. But at this moment, we were just fiddling with some ideas. We knew that whatever this workshop looked like, it would be, at best, a strong first draft of an experience we hoped would help to create crossover between “separate” domains. ((Like much good learning is.))

_______

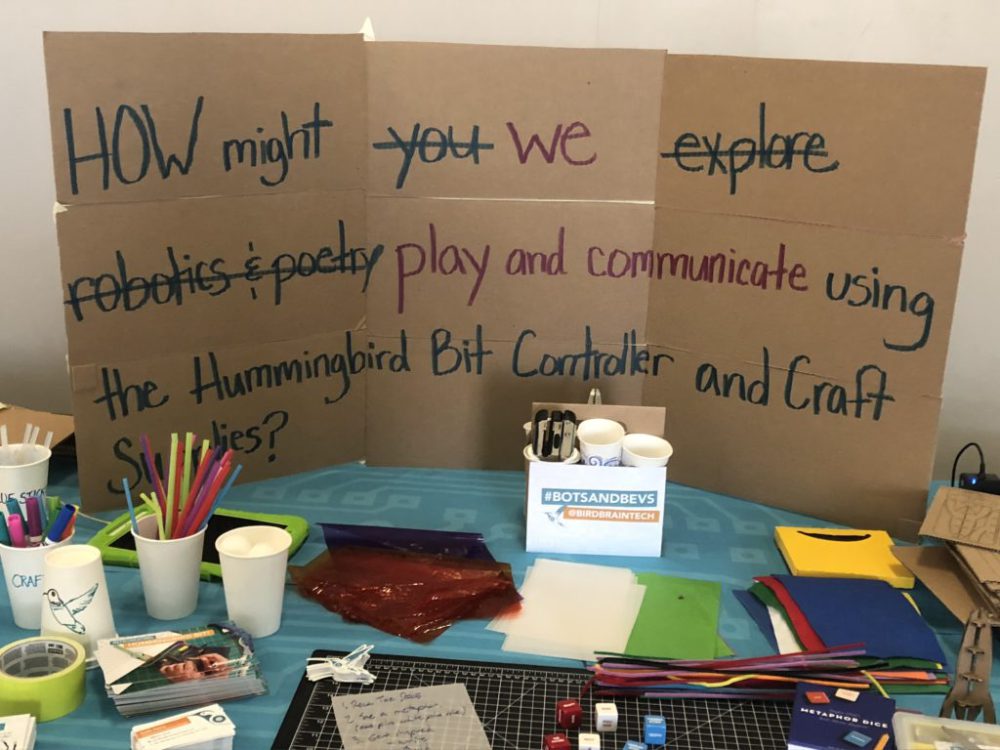

Robot Memories is a self-directed craft robot building experience for absolute beginners. In about one hour, participants re-create a favorite memory using the Hummingbird Bit compositional tool kit and craft supplies.

In the experience, we ask the Maker to first focus on a favorite memory (or shared memory if working with a partner). Next we introduce tools that might be used to recreate the memory, such as craft supplies, handwriting tools, LEDs, Motors, and the Hummingbird Bit.

We’ve noticed that even in a short period of time (one hour), absolute beginners tend to create more nuanced and intricate robots than if they had a standard 3 or 6 hour introduction. I’ve seen hockey players shooting goals and Grandma rolling out cookie dough while smoking a cigarette. ((It’s interesting to see how many times the Challenger space shuttle appears in each workshop.))

_______

Learning about Robot Memories was illustrative – it reminded me that when the learner is the entry point, and not hardware or conventions or writerly things, it’s easier for the learner to remain in control of the experience. When we start from tools, too often, the tools get to drive. ((“Can I do X?” when asked of a tool requires external expertise. “Can I do X?” when asked of a thing someone is creating, well, that requires the creator to answer the question. See the difference?))

Good writing is like that. When it starts from exigence rather than compliance, important things happen fast. Learners want to learn the mechanics when they are eager to get a thing made, or to define and express an experience.

When the Metaphor Dice became a thing, we saw another way to center the learner in the experience. Actually, Katie saw that way earlier than I did. As she does. I eventually came around.

The basic structure of the workshop was this:

We began by setting a quick frame of poetry and making as two branches of the same big activity. The root word of poem is the Greek poiesis, which means “to make.” I mean, come on. That’s a good frame.

Then we wrote together. Quickly. The Metaphor Dice game can lead to multiple poems being written in under ten minutes. And working from the way I learned to play the game in a makerspace at #CMK, I realized that we could layer in depth and some revision as we went along, too. So we wrote our way through three quick rounds of poem writing.

Once folks had written some poems, then Katie walked us through the basics of building a robot using the Hummingbird Bit. ((That’s some seriously generative hardware. I’ve been enjoying getting to know it better these last couple of months.)) And I mean basics. She showed them how to light up an LED and how to turn a servo. That was it. But that’s not all the hardware can do. It’s barely the beginning of it. ((What Katie knows, and modeled in her brief introduction, is that the desire to get an idea into the world is sufficient to move learners from a place of wondering to exploring. Later on in the workshop, we would help folks turn on other elements, and program beyond the very basics she covered. But not because we wanted them to know how – it was because they wanted to know how. ))

And then it was on. The challenge driving the time was to take the ideas and memories and experiences of our poems and try to turn them into robots. Or to take the ideas and memories and experiences of our robots and try to turn them into poems.

Or to mix and match and see what happened.

_______

As Parker Palmer writes, “I teach who I am” – the inner life of a teacher tremendously influences space-making decisions s/he makes in the classroom with students.

To teach teachers in a way that transfers to student-centered space-making decisions in their own classrooms is a matter of the heart. Disrupting preconceived ideas about “writing” and “robotics” in a way that makes space for a teacher’s personal hope to drive personal decision making – and explore their own inner landscape, working from the inside out – makes visible to the individual teacher (learner) an experience that might be possible for their own students.

It’s not about the robots. Or the writing. If it were, you should just build a robot and write about how that made you feel.

It’s about you, your learning, your hopes, your talents, and your growth. ((And that is really hard for some people to own – belief that I matter. When I believe that I matter, I tend to get more involved in my own learning experiences. That’s why increasing student agency in the classroom has everything to do with increasing teacher agency.))

At the end of the workshop, a high school physical science teacher who “came for the robots,” but became absorbed in writing poems asked, “Does writing usually do this to you?” He wanted his students to experience what he had experienced and through a conversation with Bud, began to realize that even in physical science, there were plenty of words to play with, too.

When I deeply care about the thing I am composing, I tend to want to get the details right. I am more perseverant and precise. ((Differentiation usually isn’t a problem in these spaces. But that’s another post.))

This is what writing (and robotics) across the curriculum can mean. ((Maybe a better way to look at this is composition across the curriculum – it’s where the learning happens.))

_______

The workshops, as three-hour total experiences, were a bit ambitious. But we started to see what we thought we might see – and will work to develop more thoughtfully the next time we facilitate this particular workshop. The writing and the robots were talking to each other through the writer/composer/maker. Tinkering in one way – with words, ideas, metaphors – led to tinkering another way – attempting to add motion, or a series of actions, etc. And vice versa. These tinkerings can inform each other. With more time, we would have intentionally driven that process a bit. Or so we decided when Katie and I were debriefing at the end of the day.

_______

Have you already been exploring the intersection of writing and robotics? If so, we’d like to learn what you’re up to. Please tell us about it in the comments.

Are you interested in exploring the intersection of writing and robotics in your own classroom? If so, we’d love to share some resources with you. Get in touch.

We’re hoping to find people, partners and a place to try this workshop again, possibly for a longer period of time. Not sure where, but this experience needs to happen again. We are looking forward to more chances to fiddle with the intersection of composition and robotics.

_______

There’s plenty in composition that transcends modality. And composing with servos and circuit boards isn’t that different from tinkering with words. Anything we can do to help students and teachers see that, and experience it, and create spaces for others to do the same, is a big step forward into better learning experiences for everybody.

_______

Composition, after all, is where the learning happens.