This is a post in two voices that lives in two places. You can read the other version at Bud’s website. In this version, my voice appears in italics and @budtheteacher‘s is in the other.

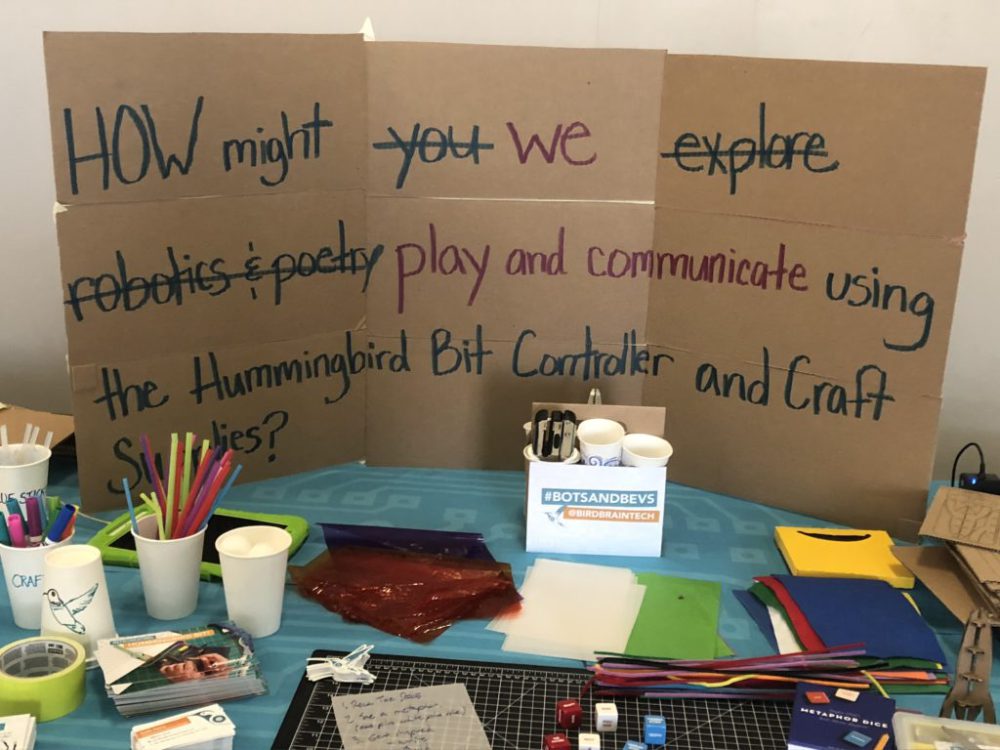

It’s been a few weeks now since Katie Henry and I met up at reMAKE Education to run two sessions of a workshop that has me more excited than I’ve been about a workshop in a long time. I’ll get to the excitement part – but first, a bit on how this came to be.

It’s actually quite a story. And it starts, not with a conference proposal, but with a business card. No, that’s not true. It begins with a brownie.

Continue reading “A First Draft In Two Voices”